Click images to enlarge.

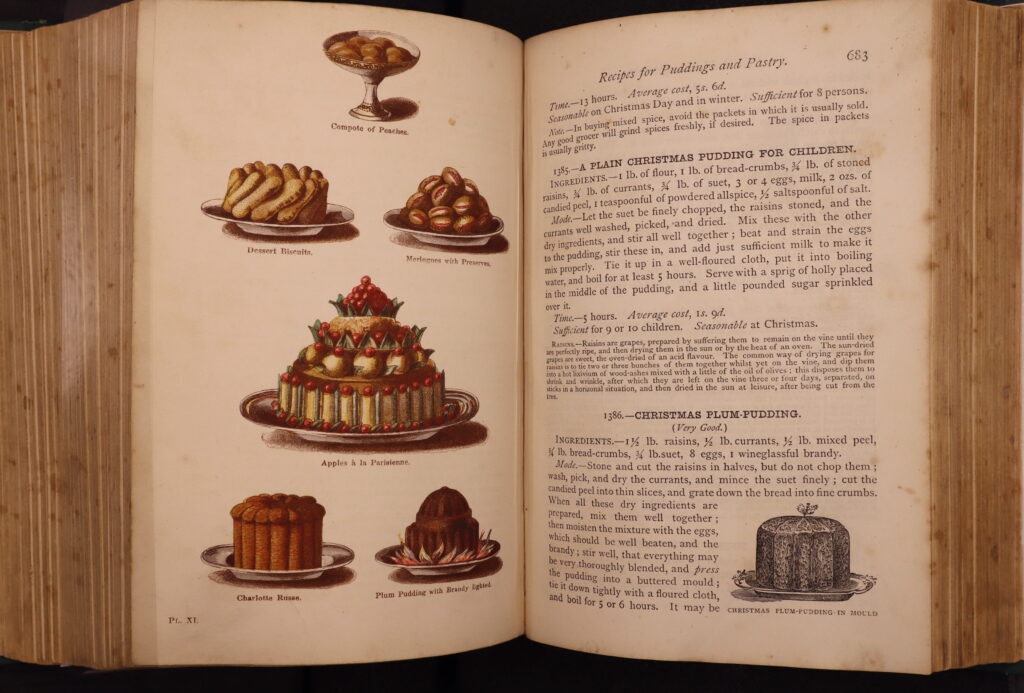

Isabella Mayson Beeton (1836–65), known very properly as “Mrs. Beeton,” was a journalist at a time in which many editors of the flourishing periodical press welcomed female contributors and the market for middle-class female readers (of magazines, journals, and novels) was burgeoning. In 1852, her future husband, Samuel Beeton, launched English Woman’s Domestic Magazine; she began contributing in 1857 and became its “editress.” She also contributed to The Queen, launched in 1862. She is best known for Beeton’s Book of Household Management, issued serially from 1859 to 1861 and published as a fully illustrated volume in 1861. As Janette Ryan summarizes, the “book’s style moved easily between detailed instructions and neat aphorisms.” More than a collection of recipes and domestic bromides, however, the book taught readers home economics, health standards, common sense, sensible cuisine, and respect for women.

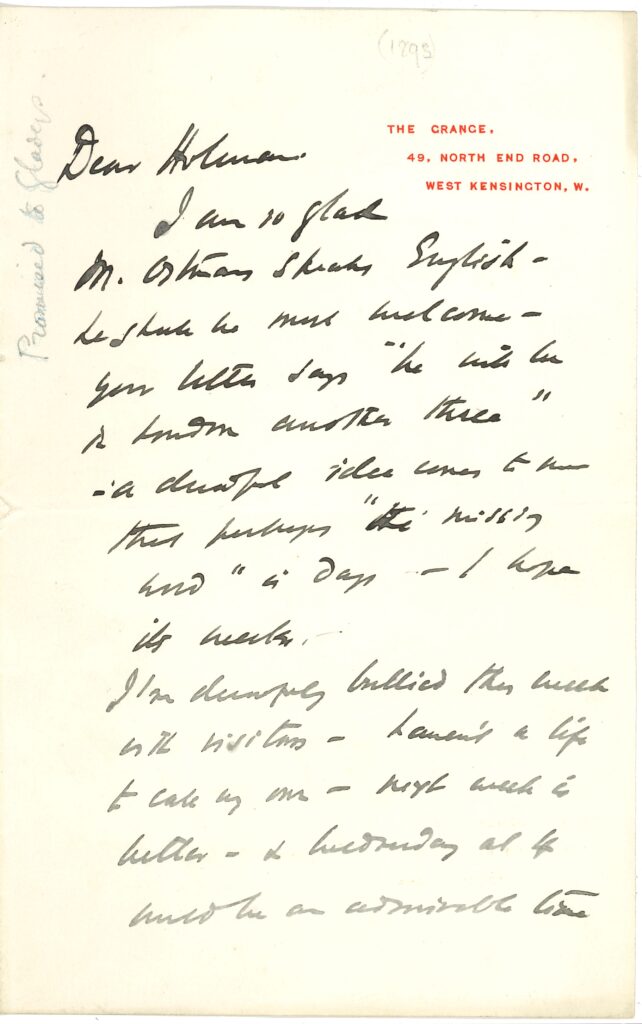

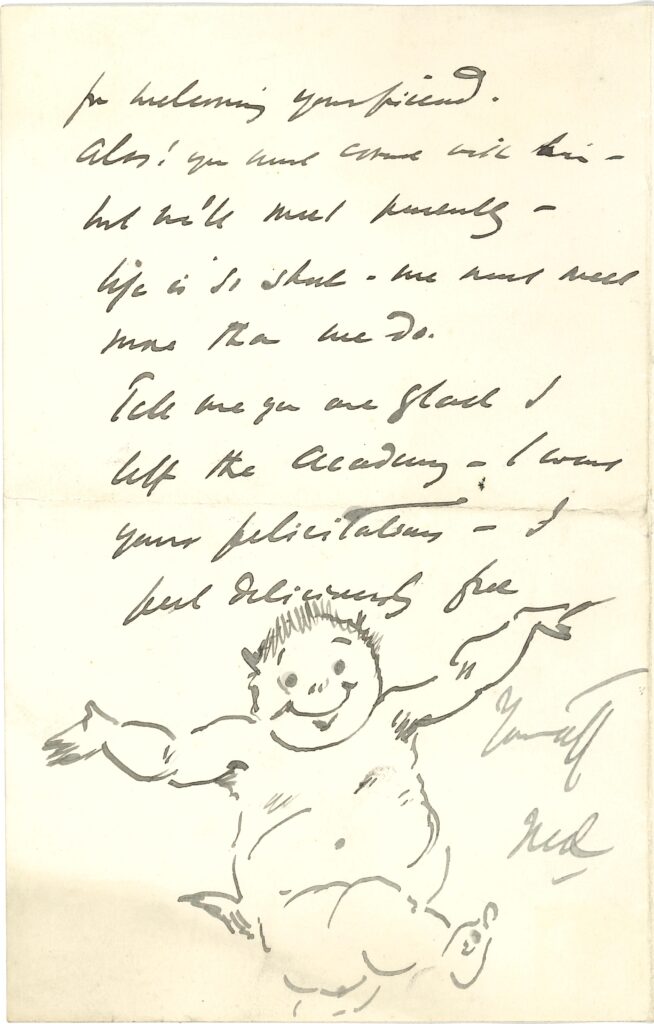

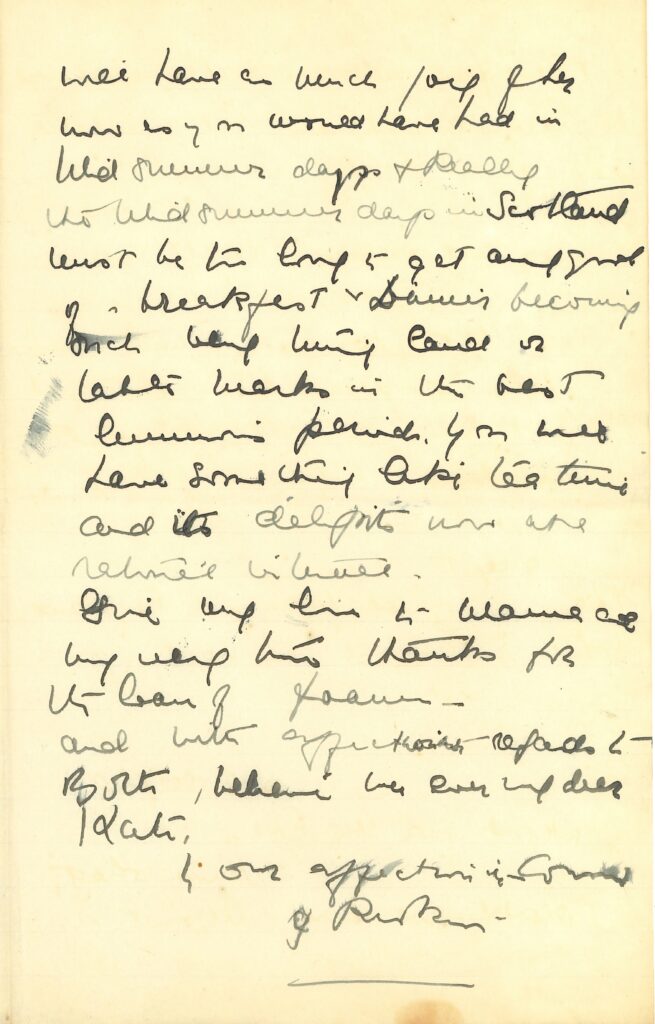

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones to William Holman Hunt. 2011-049/001(04), Clara Thomas Archives collection (F0486), Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections.

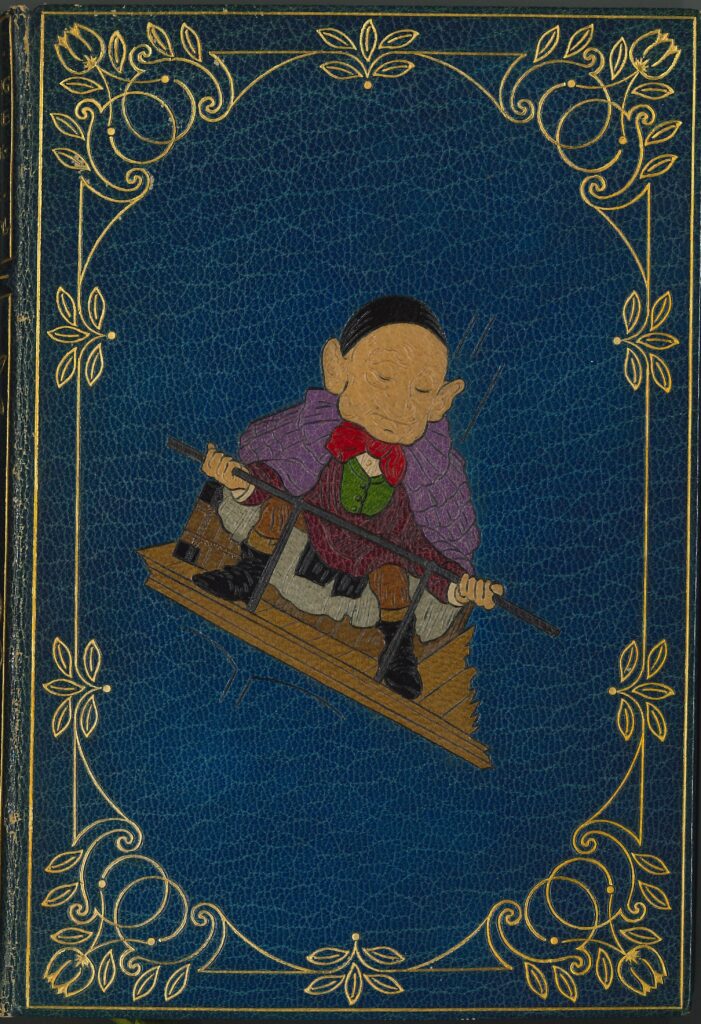

Sir Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898), born in Birmingham, met William Morris at Oxford, where the two soon became leaders of the Pre-Raphaelite movement. Burne-Jones led with his oil paintings of Arthurian mythology, but also with his decorative designs for furniture and stained glass and for his book illustrations, calling the Kelmscott Press books on which he and Morris collaborated “pocket cathedrals.” In this 1893 letter to his Pre-Raphaelite colleague William Holman Hunt, Burne-Jones urges them to meet more often. He concludes with a self-portrait that caricatures the delight he feels having resigned from the Royal Academy, feeling like a reborn cherub, wingless, but ready to hop, skip, and soar with his tailfeathers and out-stretched arms.

Charles Dodgson (1832–98) might have been remembered as a discerning mathematician (and Euclid specialist) at the University of Oxford, an excellent amateur photographer, and a good preacher (he was ordained a deacon in 1861 because Oxford dons were then required to be clerics). As Lewis Carroll, however, he achieved international fame for his children’s books: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There(1871), and The Hunting of the Snark (1876). He also published three volumes of verse. His academic publications included A syllabus of plane algebraical geometry (1860), Euclid and his Modern Rivals (1879), and Curiosa mathematica (1888–89). To numerous humour and entertainment journals, including Punch, Vanity Fair, and Dickens’s All The Year Round, he contributed games, puzzles, and comic verse. His games and mind-teasers were published in Castle-Croquet (1866), Mischmasch (1881), and several other volumes.

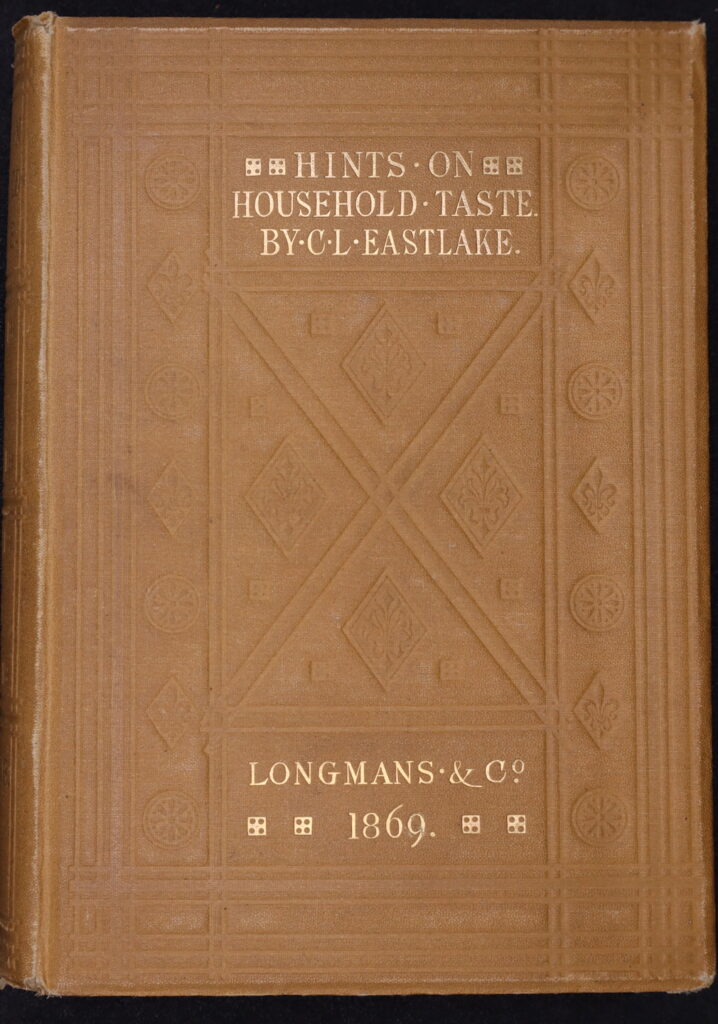

Charles Eastlake (1836–1906) trained as an architect but was successful as a well-known British furniture designer and architectural writer. Eastlake helped to popularize William Morris’s Arts and Crafts style and promoted the importance of the decorative arts. His works on furniture design were influential in Britain and the United States, as was his 1872 study, The History of the Gothic Revival. He was keeper of the National Gallery in London from 1878 to 1898. (His uncle, Sir Charles Lock Eastlake [1793–1865], a painter and art historian, was the first director of the National Gallery, 1855–65.)

Kate Greenaway (1846–1901) enrolled at the Finsbury School of Art at age 12; she studied there six years. Her earliest works as an illustrator appeared in the late 1860s; she first exhibited at the Dudley Gallery in 1868. In 1869, she was commissioned to produce six watercolours for Frederick Warne’s children’s book, Diamonds and Toads. For almost a decade, she worked for Ward & Co., but the publisher was not interested in her texts that featured drawings and verse. Edmund Evans, however, published Under the Window in 1879. In the 1880s, John Ruskin became a mentor. Among her major successes: Kate Greenaway’s Birthday Book (1880); Mother Goose, or, The Old Nursery Rhymes; and A Day in a Child’s Life (1881). Subsequently she illustrated almanacks, readers, books of verse, and Robert Browning’s Pied Piper of Hamelin (1888).

Myles Birket Foster (1825–99) was a British artist and engraver. While apprenticed to well-known wood-engrave Ebenezer Landells, he produced works for Punch magazine and the London Illustrated News. He illustrated Henry Longfellow’s Evangeline and became well-known for his watercolours of rural life and children (in the 1860s and 1870s, more than 400 of his works were exhibited at the Royal Academy). His friends included Edward Burne-Jones, William Morris, and Frederick Walker.

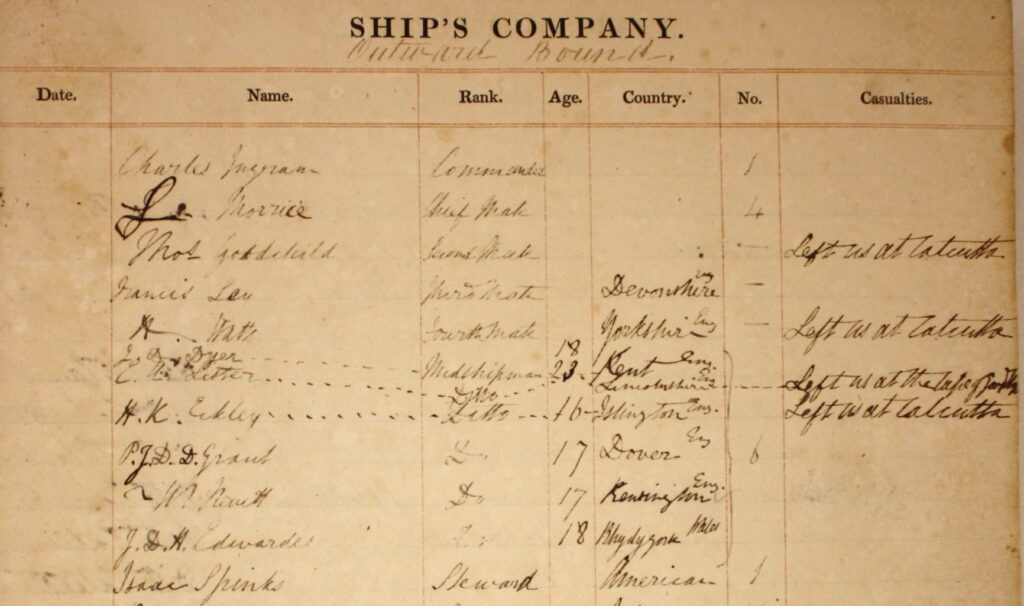

Built in 1808, Larkins was a 129-foot (39-metre) wooden ship that carried up to 50 men. As an East India Company ship, it made numerous voyages to India, as well as three chartered trips bearing transported convicts to Australia. Such journeys could take three to five months, depending on winds, weather conditions, and the individual ship. While some argued that the use of steam power could greatly reduce travel time, a trial run with a steamship in the 1820s still took three months to reach Calcutta.

These logbooks provided a record of the journey, detailing weather and wind conditions, and recording the names of an international crew made up of English, French, German, Irish, and Dutch sailors, as well as the identities of passengers, which included military men, missionaries, American civil servants, and wives traveling from India back to England. But they also offer a window into everyday life on the ship. Crew members contributed sketches of other sailing vessels, reflections on the passengers’ health and dispositions, and accounts of incidents such as drunkenness or ill health, and they pasted in miscellaneous news clippings that might have reminded them of life back home.

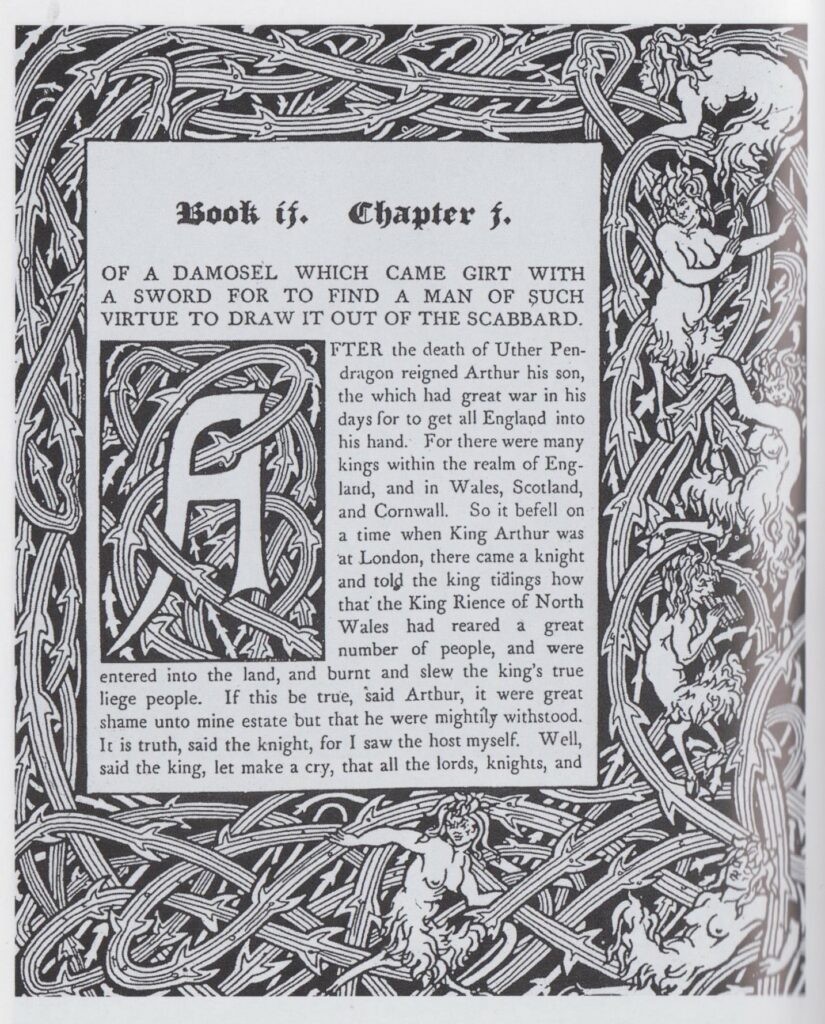

12341 Malory, Thomas, John Rhys, and Aubrey Beardsley. The Birth, Life, and Acts of King Arthur, of His Noble Knights of the Round Table, Their Marvellous Enquests and Adventures, the Achieving of the San Greal, and in the End, Le Morte Darthur. London: J. M. Dent], 1893–1894.

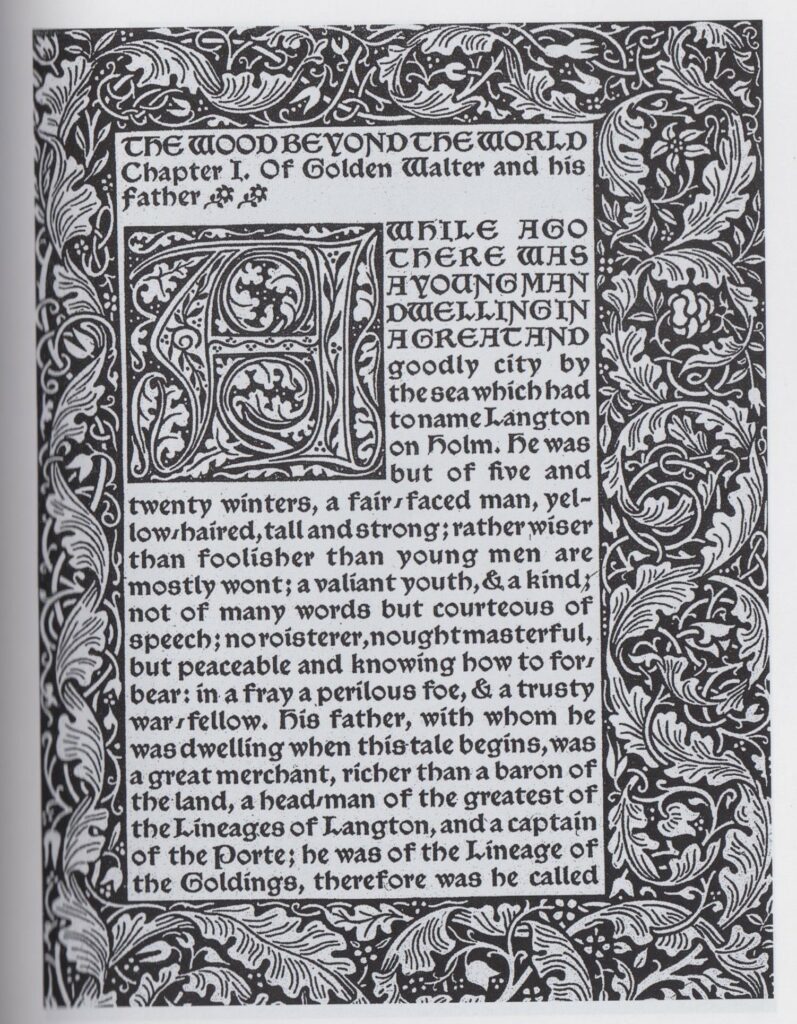

A comparison of William Morris’s (1834–1896) book design for his Kelmscott Press (1891), at right, with Aubrey Beardsley’s (1872–1898) book design commissioned for an edition of Malory’s Morte D’arthur (1893–1894), at left, showcases the difference between Morris’s Arts and Crafts style and Beardsley’s decadent parody.

Beardsley follows Morris’s example by framing the text with a decorative border and then repeating that border as an inner frame whose foliage is intertwined with the opening initial. Morris’s curved stems with leaves and blossoms are circular like halos; Beardsley’s thick stems with thorns and satyrs are coiled like serpents. Morris’s initial is rounded; Beardsley’s initial extends downward like a sabre through the thorns. His androgynous satyrs scowl and crouch and crawl. Morris’s design is one of organic growth, suggesting the walled garden of paradise. Beardsley’s design is a demonic artifice, aggressive and menacing. His overemphasis on ornament at the expense of naturalistic detail makes his art appear overly sophisticated. It thus exemplifies what Morris called the “disunion” of the intrusively artificial. Beardsley’s parodic design bears no trace of Morris’s faith in a paradise regained through the integration of aesthetic and social principles.

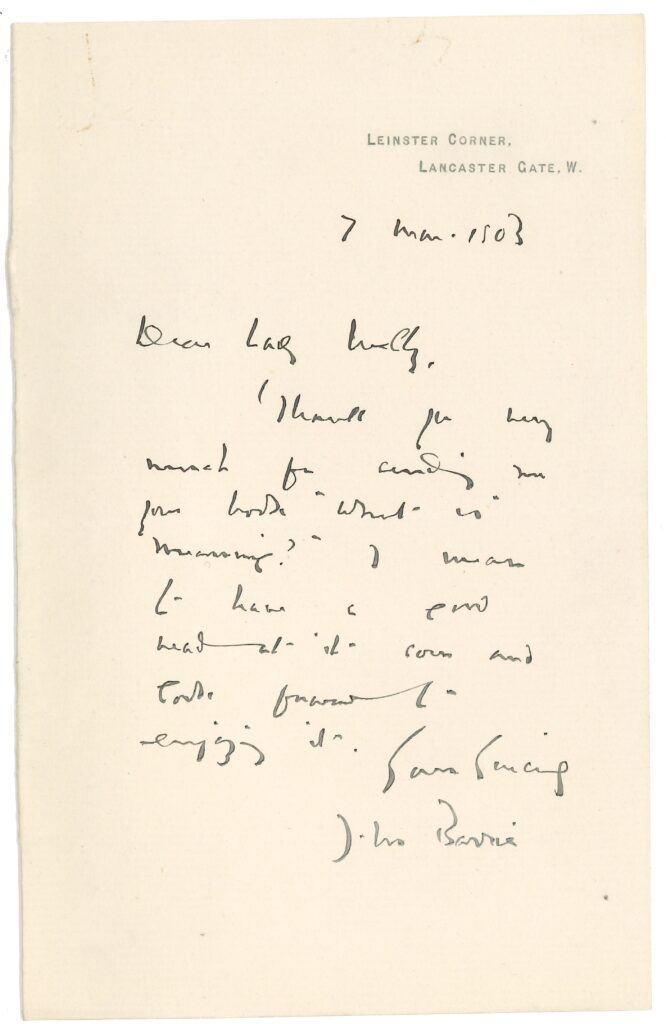

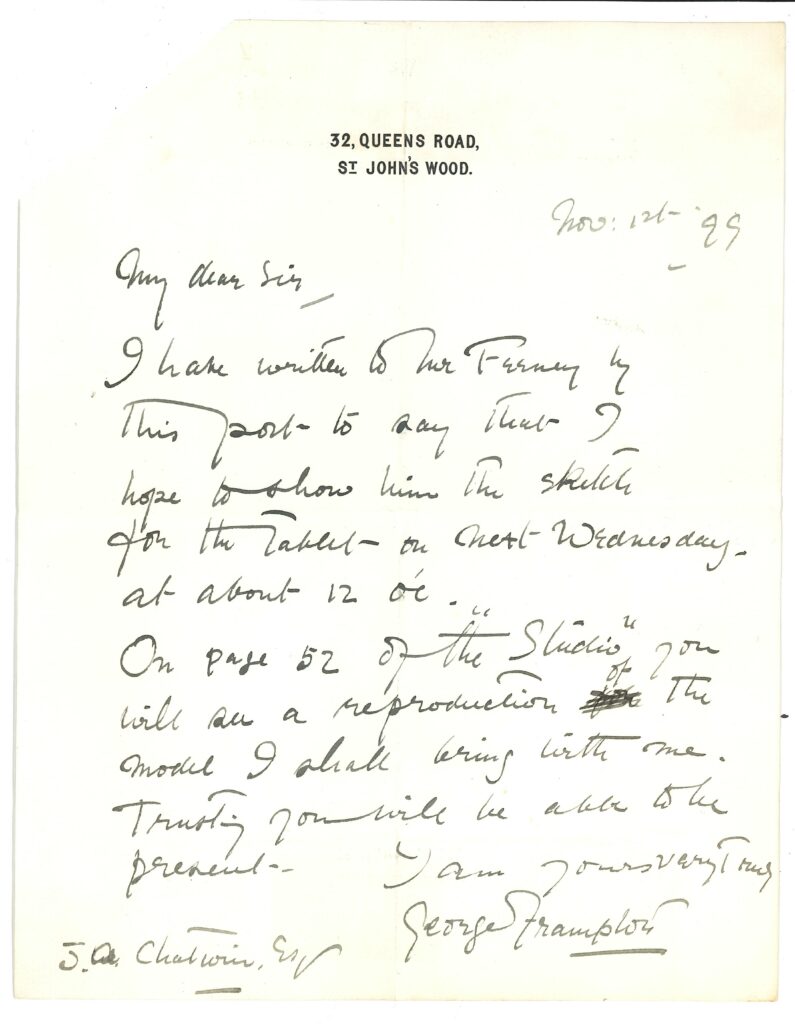

Letter (left): Barrie, J. M. to Victoria Welby, 1903. 1970-010/001(24). Lady Victoria Welby fonds (F0443), Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections. Letter(centre): George Frampton to J.A. Chatwin, November 1, 1899. 2011-049/001(05). Clara Thomas Archives collection (F0486), Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections. Photograph (right): Northwest corner of Avenue Road and St. Clair Avenue West, statue of Peter Pan (Item 716). October 4, 1929. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1231, Item 716.

Sir James M. Barrie (1860–1937), born in Kirriemuir, Scotland, was a dramatist – Ibsen’s Ghost ((1891), The Admirable Crichton (1902), and Peter Pan, or, The Boy Who Would Not Grow Up (1904) – and a novelist, first introducing Peter Pan as a character in his novel The Little White Bird (1902).

Sir George Frampton (1860–1928), born in London, was the leader of the New Sculpture movement of the 1890s. His bronze statue of Peter Pan (1912) stands 14 feet tall in Kensington Gardens (where much of J.M. Barrie’s play is set); Frampton provided the city of Toronto with a copy of Peter Pan located in what is now named Glenn Gould Park, at the intersection of Avenue Road and St. Clair Avenue West.

The Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collections also hold a letter from Sir Edmund Gosse (not shown here):

Edmund Gosse (1849–1928) – librarian, biographer, essayist, and Pre-Raphaelite poet – was the leading critic of the New Sculpture movement, a term Gosse coined in 1894 for a stylized sculpture that combines elements of Arts and Crafts, Art Nouveau, and Symbolism.

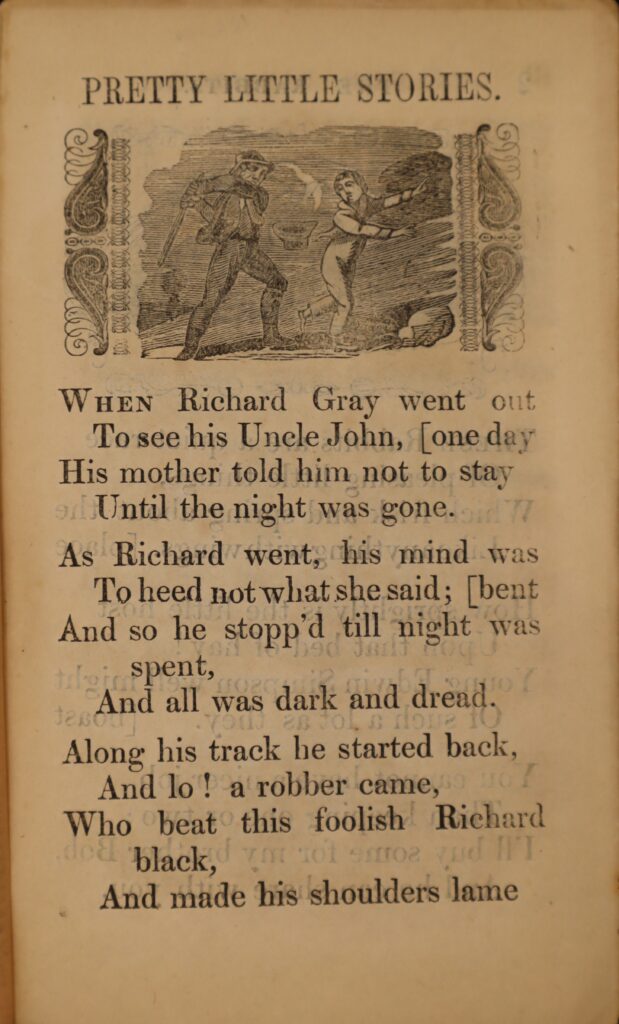

Walker and Son, a northern English publisher of religious works, children’s literature, ballads, and almanacs, was active in the first half of the nineteenth century. Like their abridged version of Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (also on display here), this inexpensively printed work was intended for young readers. Pretty Little Stories includes eight pages of simple poems, each adorned with a woodcut illustration. As a group, these rhymes reinforce the values of perseverance, sobriety, obedience, and seriousness, even as they also celebrate the value of well-earned leisure time, familial bonds, and consumer choice.

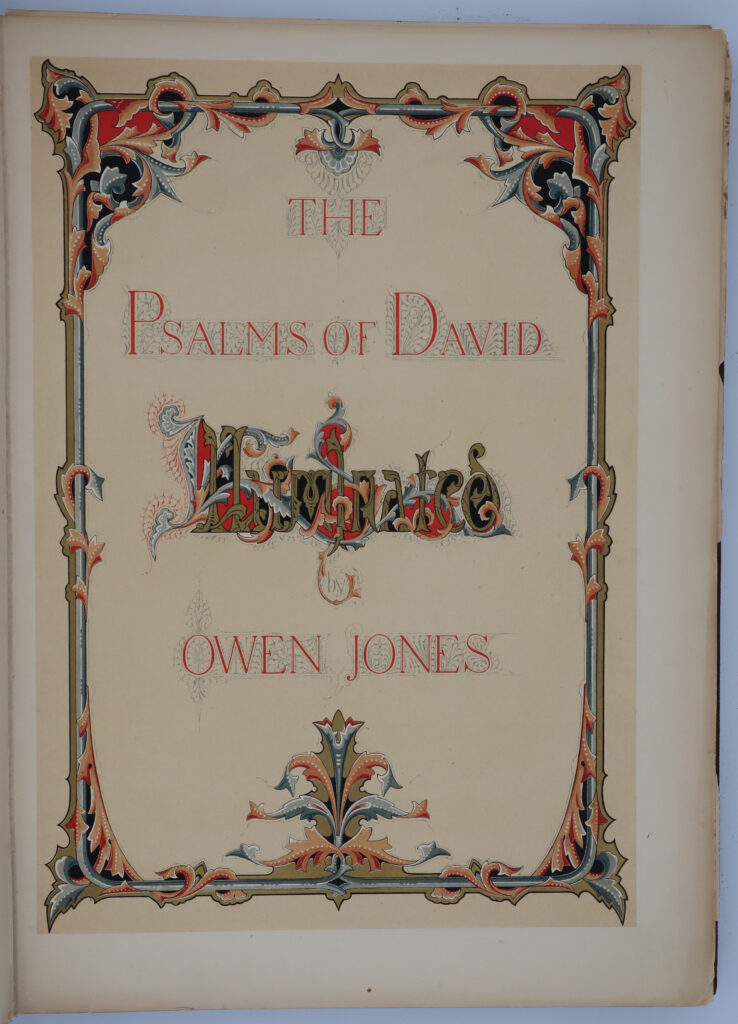

Whether written by King David or not, the Psalms of the Old Testament express religious devotion with poetic grace. Many are tributes to the deity (“Sing unto the Lord a new song”); many are lamentations for Israel or the speaker who cries for remediation (“leave not my soul destitute”). Major themes include the Creator and his creation, the future of Israel, the necessity and burden of the law, and prayers for mercy. This 1861 volume is one of several parts of a collection that, in 1885, was published together as The Victoria Psalter, an illuminated book dedicated to Queen Victoria.

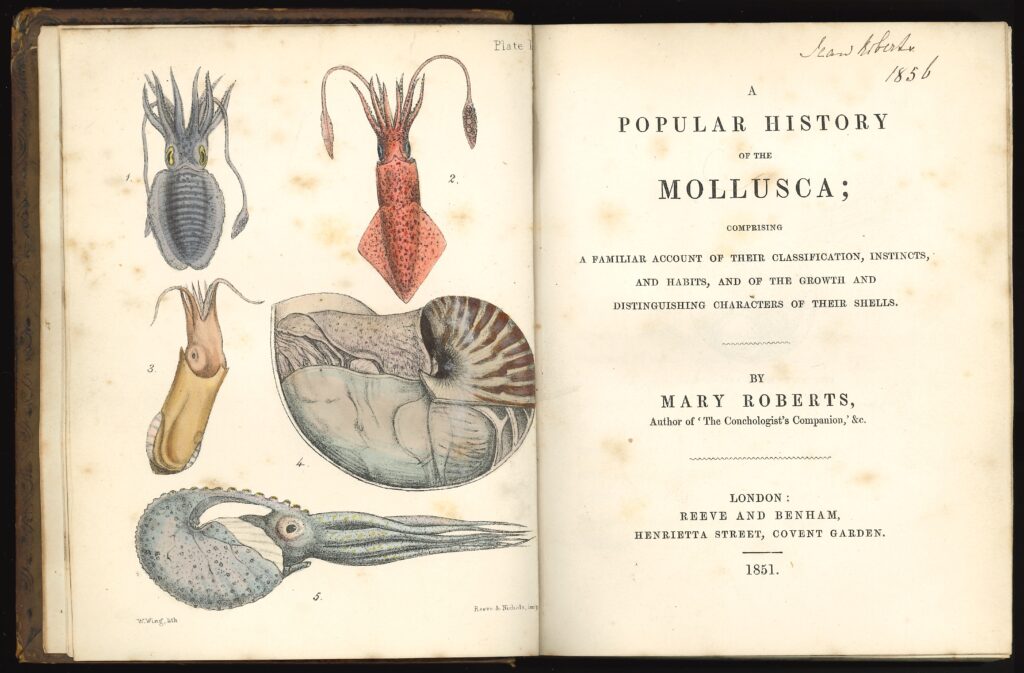

Like her contemporaries Mary Kirby and Jane Loudon, Mary Roberts (1788–1864) turned to popular science writing as a way of supporting herself after her father’s death. She published more than ten works of natural history, among them the especially successful Domesticated Animals, which first appeared in 1833 and remained in print decades later. Raised as a Quaker, Roberts was deeply religious, and her writings, like those of many scientists and science writers of the period, reflected a belief that signs of providential design and divine influence could be found throughout the natural world. In her A Popular History of the Mollusca, she invites the lay reader to share her appreciation for the biological and aesthetic qualities of creatures so “carefully wrought for the place and station which they are designed to fill.”

2005-050/001(02), Cameron family fonds (F0493), Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections

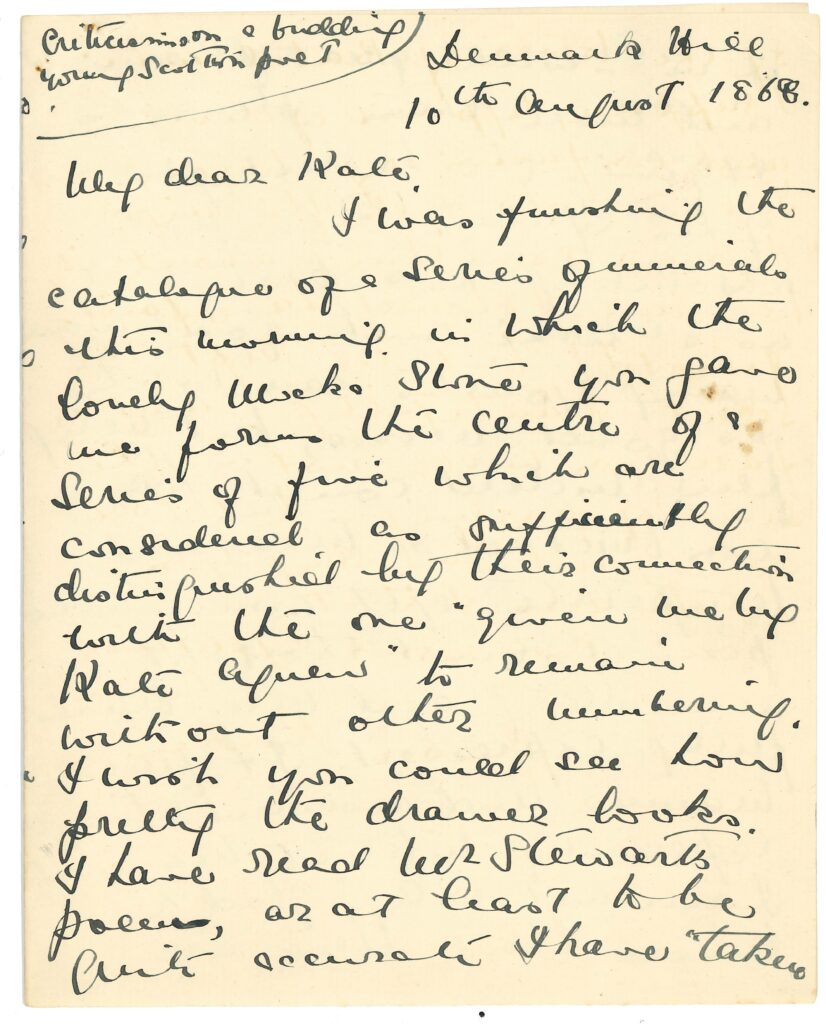

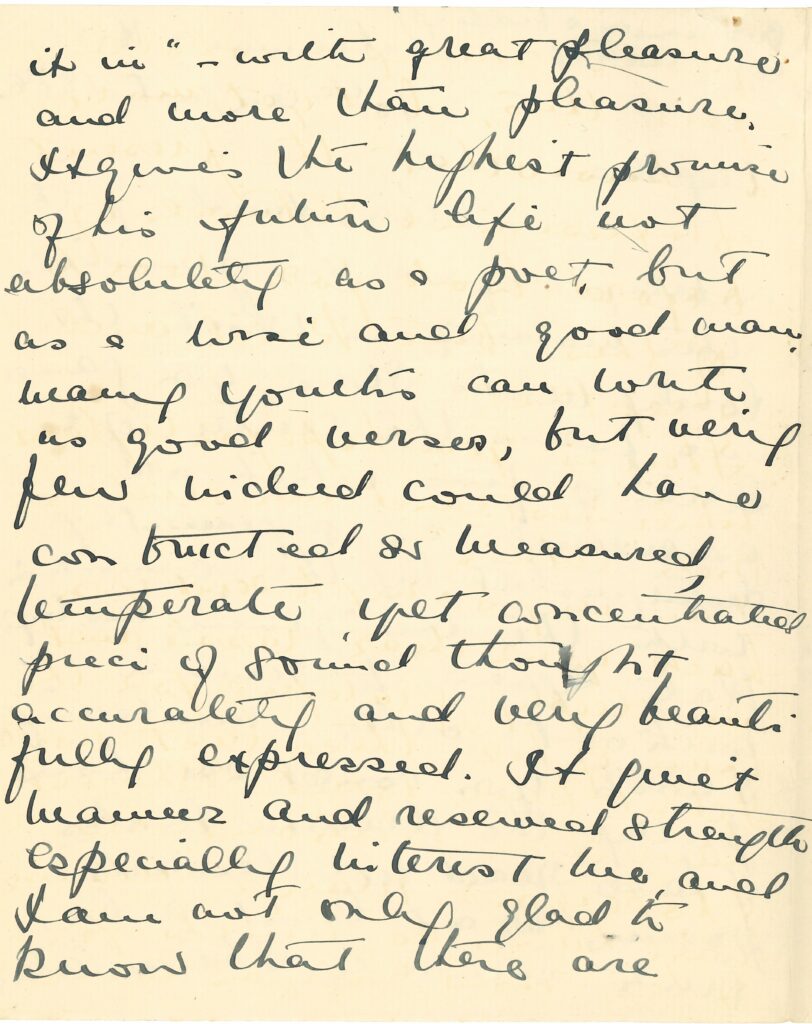

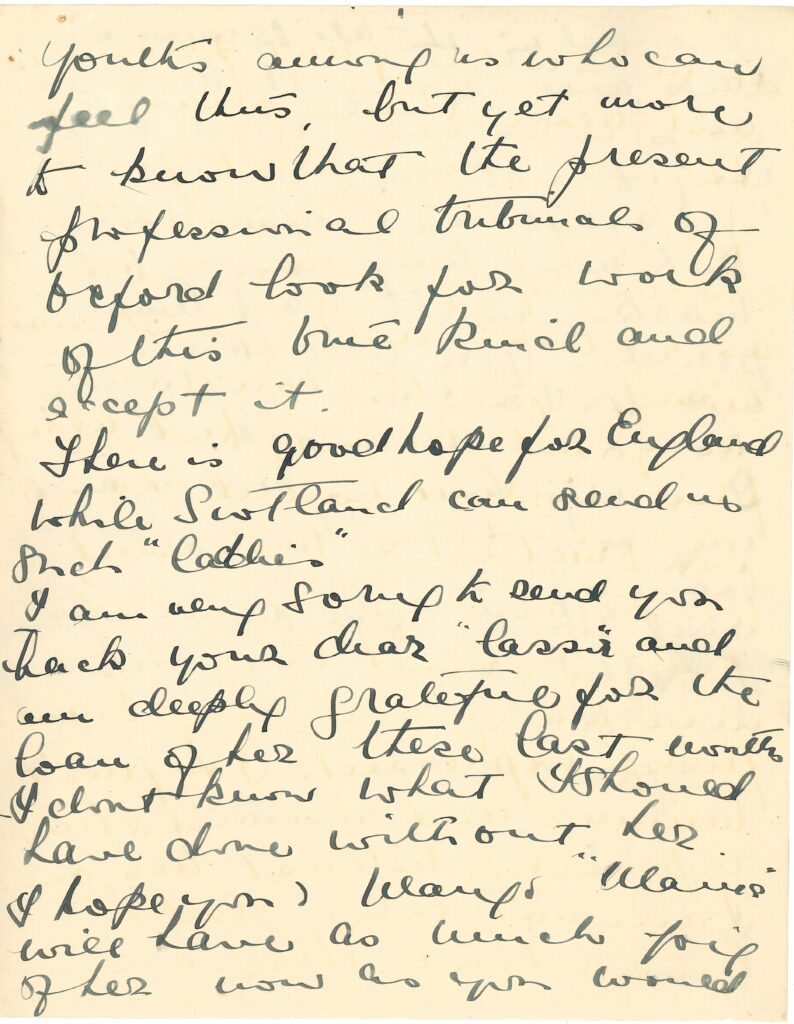

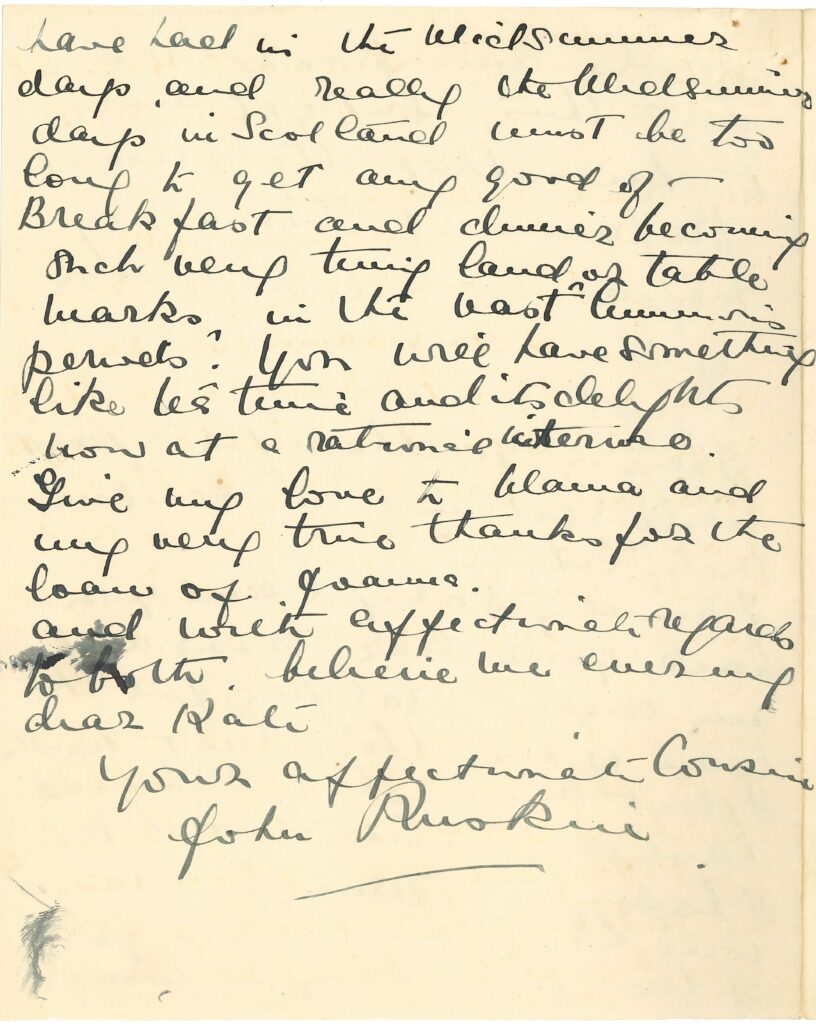

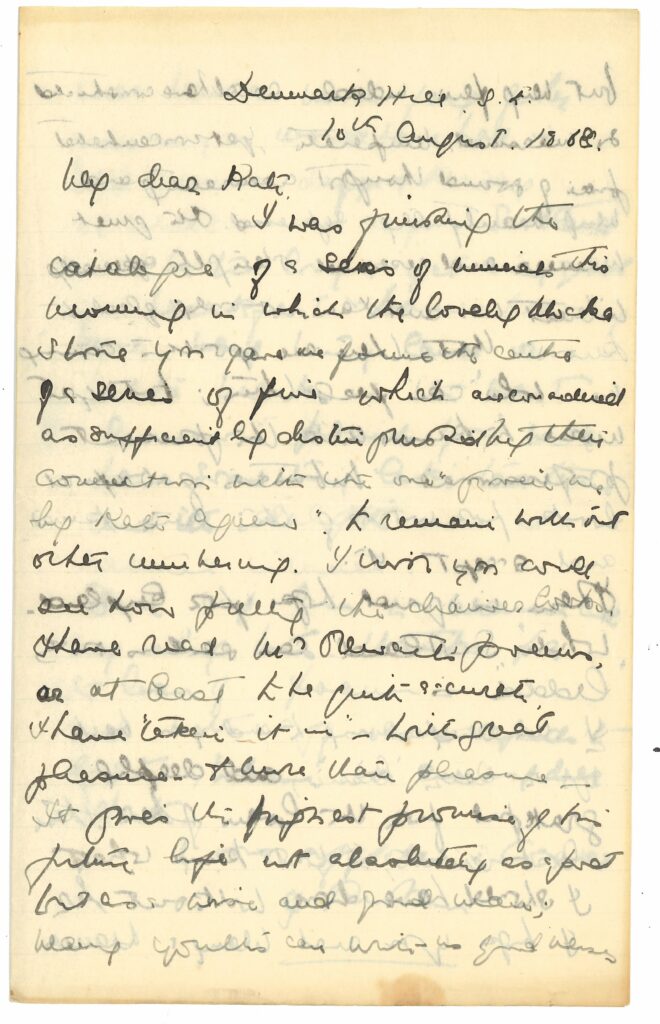

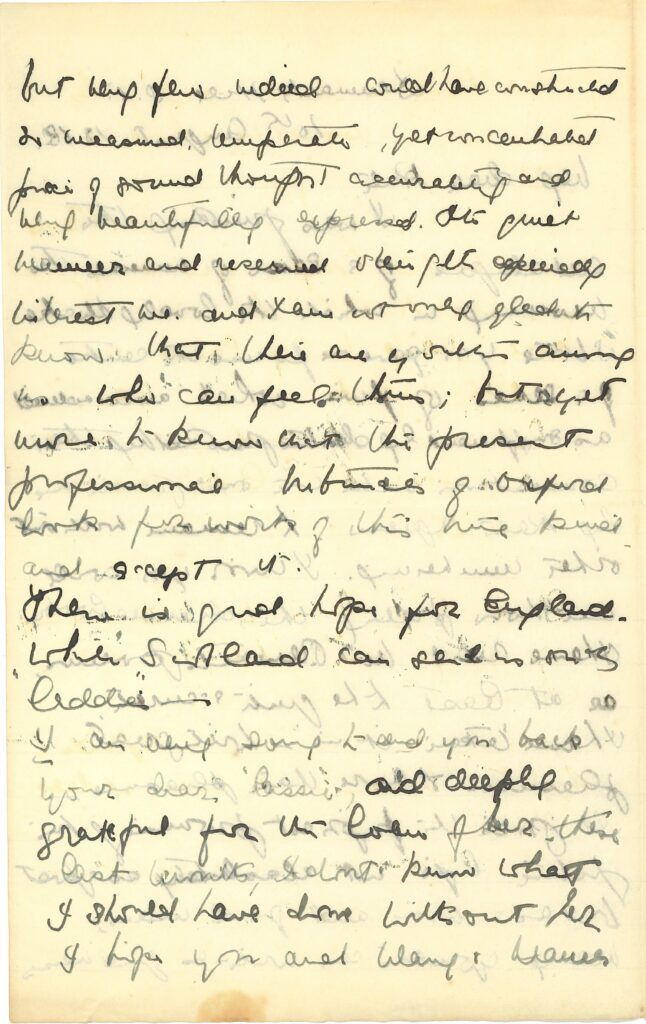

John Ruskin (1819–1900) was homeschooled until he enrolled at the University of Oxford where he won the Newdigate Prize in poetry. His influential books on art and social theory ranged from Modern Painters (five volumes, 1843–60) and The Stones of Venice (three volumes, 1851–53) to The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century (1884). He championed the artist J.M.W. Turner, the young generation of Pre-Raphaelite artists, and the Gothic tradition in architecture over the conformity implicit in classical and Renaissance architecture, arguing that the Gothic provided the architect and the stonecutter an equal freedom of artistic expression.

Our manuscript collection at York includes six Ruskin letters and an inscribed volume. For five of the letters, we have five drafts and five fair copies, indicating his practice of hastily composing each letter and then copying each one before saving the draft and posting the copy. We include here a letter drafted to Kate Townley on 10 August 1868 (above) and his fair copy dated the same day (below).

2005-050/001(03), Cameron family fonds (F0493), Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections

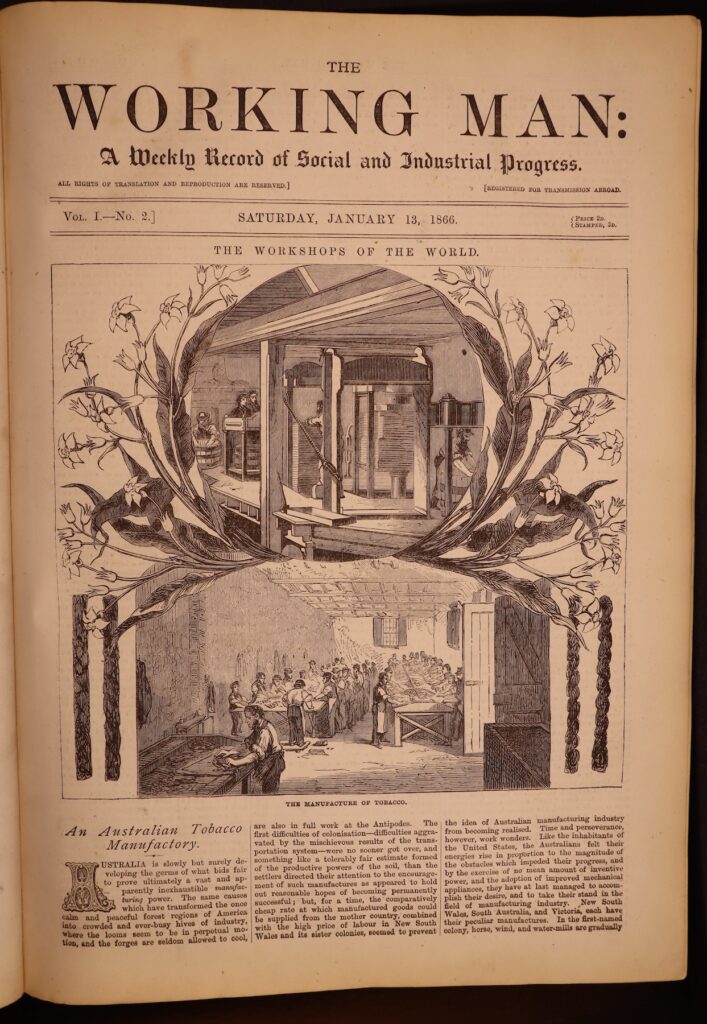

Appearing weekly in the year before the passage of the Second Reform Bill (1867), which effectively doubled the number of men empowered to vote in parliamentary elections, The Working Man: A Weekly Record of Social Progress and Industrial Progress capitalized on public interest in machine and artisanal production. Its illustrated pages contained analyses of mechanical, architectural, and interior design; information about regional and national differences in wages; announcements of employment opportunities in the colonies; discussions of workers’ housing, and advertisements for consumer items such as life insurance, crinolines, and pocket watches.

The Working Man followed in the footsteps of contemporaneous publications such as George Dodd’s illustrated “Days at the Factories” series, which appeared in The Penny Magazine from 1841 to 1844, and a similar set of articles published starting in 1863 in the British Trade Journal, and also spoke to a readership that might have attended the 1851 Great Exhibition and the 1862 International Exhibition of Industry and Art in London.

The World of Fashion and Continental Feuilletons was an elegant monthly magazine that featured articles on art, literature, and music, alongside “gossip and the gaieties of High Life,” and was fully illustrated with steel engravings of ladies’ fashion. (The periodical documents the changing fashions of dress.) Later fashion magazines would be edited by the leading literary writers like Oscar Wilde (Woman’s World, 1887–1889), who considered his magazine “the first social magazine for women,” and Rosamund Marriott Watson (Sylvia’s Journal, 1892). John Fowles, in the opening chapter of his 1969 novel The French Lieutenant’s Woman, exploits the diction of political revolutionaries to describe the importance of Victorian fashion in 1867: “The young lady was dressed in the height of fashion, for another wind was blowing in 1867: the beginning of a revolt against the crinoline and the large bonnet. The eye in the telescope might have glimpsed a magenta skirt of an almost daring narrowness—and shortness, since two white ankles could be seen beneath the rich green coat and above the black boots that delicately trod the revetment; and perched over the netted chignon, one of the impertinent little flat ‘pork-pie’ hats with a delicate tuft of egret plumes at the side—a millinery style that the resident ladies of Lyme would not dare to wear for at least another year; while the taller man, impeccably in a light grey, with his top hat held in his free hand, had severely reduced his dundrearies, which the arbiters of the best English male fashion had declared a shade vulgar that is, risible to the foreigner a year or two previously. The colours of the young lady’s clothes would strike us today as distinctly strident; but the world was then in the first fine throes of the discovery of aniline dyes. And what the feminine, by way of compensation for so much else in her expected behaviour, demanded of a colour was brilliance, not discretion.”

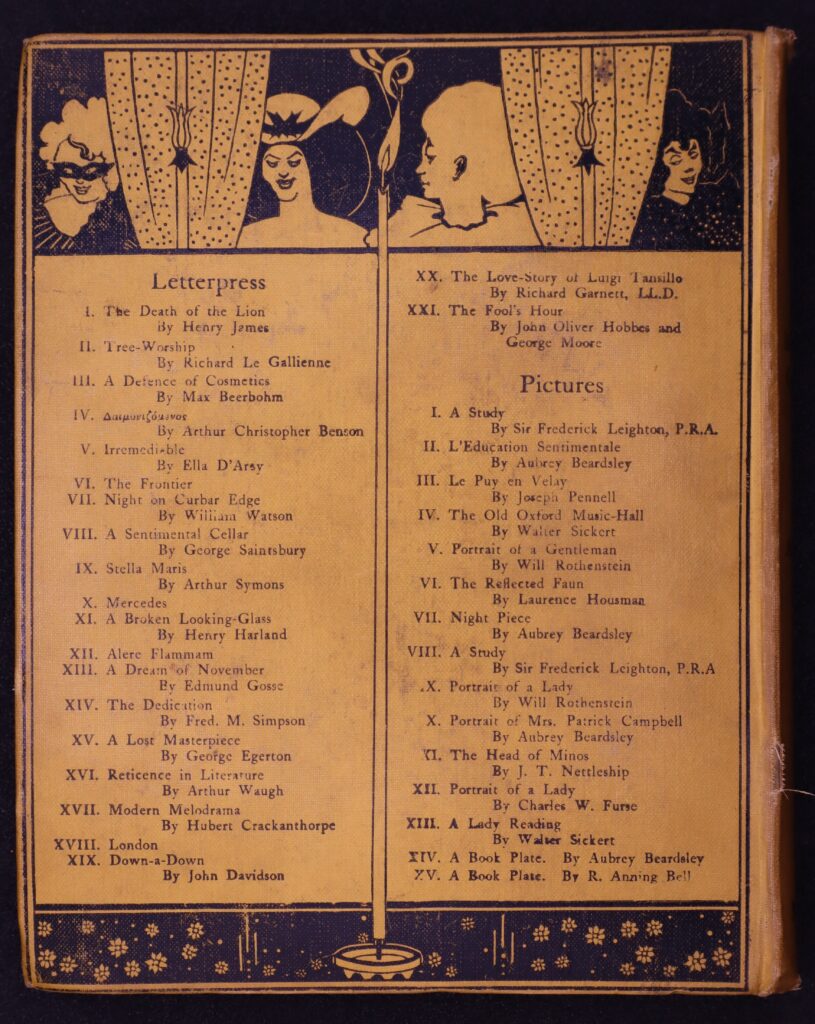

Everything about The Yellow Book seemed decadent and daring: the lavish, overtly sensual illustrations by Aubrey Beardsley, the journal’s art editor; the prose and poetry contributed by Oscar Wilde, Arthur Symons, Vernon Lee, Ada Leverson, and many others; even the disturbing, sometimes outré black and yellow covers, many by Beardsley. Edited by Henry Harland and published by John Lane (co-founder of the Bodley Head publishing firm), The Yellow Book was in print for only three years, 1894–97, but its cultural impact reverberated for decades, and has, in the last thirty years, become a staple of fin-de-siècle studies. “The Yellow Book was indeed a handsome production. Cloth-bound and numbering 250 octavo pages, each issue was priced at five shillings, at a time when many novels cost 3s. 6d. and most illustrated weeklies could be had for sixpence. Thirteen volumes of the periodical were published between April 1894 and April 1897, with new issues each January, April, July, and October” (Matthew Sturgis).